[ Synopsis ] On 22 December 1997, forty-five indigenous residents of the small southern Mexican village of Acteal were attending a prayer meeting in their village church when they were slaughtered by unknown paramilitary forces. They were members of the pacifist group Las Abejas (the Bees), who were supporters of the revolutionary Zapatistas, but who renounced their violent methods. The investigation into their deaths quickly went suspiciously cold. But what clearly and fairly quickly emerged was the link between the paramilitaries and the Mexican Government at the time.

[ Synopsis ] On 22 December 1997, forty-five indigenous residents of the small southern Mexican village of Acteal were attending a prayer meeting in their village church when they were slaughtered by unknown paramilitary forces. They were members of the pacifist group Las Abejas (the Bees), who were supporters of the revolutionary Zapatistas, but who renounced their violent methods. The investigation into their deaths quickly went suspiciously cold. But what clearly and fairly quickly emerged was the link between the paramilitaries and the Mexican Government at the time.

A decade later, Nick Higgins, expert on Mexican culture and politics, pays homage to the people of Chiapas, and sounds an alarm about what’s not right in the Mexican economic boom (and at Yale University, it could be added). To know some more: http://www.massacreforetold.com

Spectre Films: Could you tell me about the background to the film? What were you doing in Mexico at the time the massacre occurred? Were you there filming?

Nick Higgins: I was in Chiapas doing research in the field for my doctorate, as visiting researcher at an institute called the Colegio de Mexico. This entitled me to a special visa that allowed me to pass through roadblocks there. The results of that led to a book called Understanding the Chiapas rebellion, published by the University of Texas Press, but at that time I was just doing general research on the Zapatista movement. Because I could pass by these roadblocks, when I heard about the massacre in Acteal I decided I would go up and see if I could speak to people there. I arrived about a week afterwards and spoke to some of the survivors. At that point, there were two things that struck me. Their incredible ability to forgive; there was no talk of revenge at all. They wanted justice and even hated the people who had done this, but they did not want revenge, which I find incredibly powerful.

The second thing was about my own feelings of uselessness. I took all of this testimony and was not sure what to do with it. I remember their asking me if I could help but I was not sure how to do this. I asked how I could help and they answered back “Tell our story to the world”. And I answered, “I will, I will”. But it has taken years and I’ve always felt this sort of debt to them.

Spectre: I understand that feeling. You get a feeling of uselessness when you watch the film.

So you came after the massacre. This explains the footage you shot of this exodus of people going into the mountains. These are people that survived. In the press review, they say that these are people that are escaping. NH: The footage is not all mine. I had been living there for a year and a half 1997-98 but I was not filming at that point. The only people getting through the roadblocks were press and people like myself who had a special visa. So I knew there was all this footage, but it took me 2 years to track it down. I would go to the news and find there would be 30 seconds coverage. So I would find out who the cinematographer was and ask to see all of the rushes, and because I knew who everyone was, what time and what date things had happened, there was no illustrative archive – everything that was used was absolutely pertinent to what was going on in that part of Mexico at that time. What I was trying to show was the whole build up before the massacre, and the challenge was to show and not just tell. I didn’t want a film that was always talking about the past. I wanted to make a film that would show the incredible fear and terror that had been building up 6 months prior to the massacre. People were expecting something to happen. They were terrified

NH: The footage is not all mine. I had been living there for a year and a half 1997-98 but I was not filming at that point. The only people getting through the roadblocks were press and people like myself who had a special visa. So I knew there was all this footage, but it took me 2 years to track it down. I would go to the news and find there would be 30 seconds coverage. So I would find out who the cinematographer was and ask to see all of the rushes, and because I knew who everyone was, what time and what date things had happened, there was no illustrative archive – everything that was used was absolutely pertinent to what was going on in that part of Mexico at that time. What I was trying to show was the whole build up before the massacre, and the challenge was to show and not just tell. I didn’t want a film that was always talking about the past. I wanted to make a film that would show the incredible fear and terror that had been building up 6 months prior to the massacre. People were expecting something to happen. They were terrified

Spectre: That explains your title then. How much time elapsed before this became public knowledge in Mexico? The Mexican Attorney General put out a White Paper explaining the massacre as inter-community violence.

NH: Exactly. Very quickly, in a about a day, the news started getting out. But the problem was exactly as you said. News was hitting the headlines but they were saying that it was an inter-communal dispute that had got out of hand. That was the official story, and that official story is maintained to this day. It’s a shocking situation that hopefully the film goes some ways to rectify. Some of the people who were active in this crime have been sentenced and jailed, but they are all at low-level, and there was never any recognition that this was part of a wider strategy. The government maintains this position to the present day.

Spectre: Does the Mexican public Mexican public, really believe the official version?

NH: No. They don’t all believe it. Human rights groups and the majority of non-mainstream press knew the real story as well. In Mexico the broadcast news is very very limited as to what goes out on the air, but most people knew that this was part of a wider movement, but during that period, due to so much going on, what wasn’t always clear was that it was part of an organised strategy. In some ways it has taken a few years for people to realise that it started in the north of the state and started to spread down. They can isolate the various incidents, and of course a man has turned state witness against the previous government [the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights forced the Mexican Government to give him protection] now, and told that the army came and trained them, and provided them with guns, and the government of the time supplied the money.

Spectre: That’s the paramilitary you see in Mentiras?

NH: Yes.

Spectre: Did you do both films?

NH: Yes.

Spectre: It’s very unusual to use two films, shown back to back, to tell your story. There is Mentiras, which means “lies” and the other, A massacre foretold. Let’s look at the title. It is very ironic and it evokes a lot of things – the lies of the Mexican Government, the lies that were told to the paramilitary, and perhaps the lies in the account of the witness, where he must be whitewashing a few things. Was it a confession or was it an account? Did he realise that he had been manipulated?

NH: The interview is based on the human rights interview, the only one he has given. What you see is not complete. The long version goes into an awful lot of detail about so and so did this and so and so did that and so on, but we were only given access to this after ages and it took maybe about a year of negotiating to sit in on this interview. But we weren’t allowed to show his face, and we were not allowed to use his real voice. My problem was that I thought that these conditions weakened it so much that it could not have a place in the main film but none the less I felt the testimony was so powerful that I wanted to use it in some way. There is a peculiar ambiguity about his confession. He is not really remorseful, but there is an element whereby he feels like a victim as well, that he was trapped in a certain situation. I wanted to keep that ambiguity. We put it against Mexico City where he lives and is in the state’s witness protection scheme. The city and its advertising are all in a sense part of the big lie. Mexico is a country that is developing and very successfully, but there are lots of dirty stories about. He is just one of thousands if not millions in Mexico City. It makes you ask the question about who tells the truth and how it is told.

Spectre: There’s a part in the film when one of the Abejas reminds an armed paramilitary who is threatening him that he too is the son of an Indian. Did the he speak about this in the interview? Did he confront the fact that he had turned against his own people in a very hierarchical society?

NH: The problem for him was that he had his own family threatened. He and those like him had to leave or to join.

Spectre: By whom? NH: By the rest of the paramilitaries. What they [Government] would do was to get a leader in one of the communities who was supportive of the ruling party and ask him to recruit a few people, and then they would arm them. They would then start terrorising people, telling them that they had to give them money to buy weapons and arms or they would have to leave. This is where this massive movement of people fleeing from the north began. Sixteen thousand refugees were created during those 6 months, and more after the massacre. It was a really terrifying time. If you were there as a researcher as I was, there were always people coming towards you telling you theses stories but nonetheless, we were going forward to where violence was taking place. There was always a question of how far you could go and what was safe. The military were throwing out anyone who didn’t have the right credentials. In that period there were about 180 foreigners who were expelled from Chiapas because they did not want anyone observing what was going on. I was also working with the human rights organisation as one of their official observers because it was difficult to find anyone who could get through the blocks. Because I had this academic pass, I could get through, which was unusual.

NH: By the rest of the paramilitaries. What they [Government] would do was to get a leader in one of the communities who was supportive of the ruling party and ask him to recruit a few people, and then they would arm them. They would then start terrorising people, telling them that they had to give them money to buy weapons and arms or they would have to leave. This is where this massive movement of people fleeing from the north began. Sixteen thousand refugees were created during those 6 months, and more after the massacre. It was a really terrifying time. If you were there as a researcher as I was, there were always people coming towards you telling you theses stories but nonetheless, we were going forward to where violence was taking place. There was always a question of how far you could go and what was safe. The military were throwing out anyone who didn’t have the right credentials. In that period there were about 180 foreigners who were expelled from Chiapas because they did not want anyone observing what was going on. I was also working with the human rights organisation as one of their official observers because it was difficult to find anyone who could get through the blocks. Because I had this academic pass, I could get through, which was unusual.

Spectre: The first person accounts also contribute to making this film so vivid. I am thinking in particular of this beautiful woman …

NH: Maria.

Spectre: Yes, is she speaking in a Mayan dialect?

NH: Yes, she is speaking a Mayan language called Tzotzil. There about 7 Mayan languages spoken in Chiapas but Tzotzil is the main language of the highland area called Los Altos.

Spectre: How much time had elapsed since the massacre and your interview with her?

NH: Quite a period actually. That interview was made in April 2006. Maria lost nine members of her family, so the community protects her. She does not really give interviews and I don’t think she had given one for a long time before the one you see in the film. And that did not take place until several years afterwards. I had also known her for several years

Researchers would always ask where she lived, and people would say that she lived very far away while in fact she lives in a house just behind the centre. But I knew they protected her and it took me two years to pluck up the courage to ask. It was all about building a relationship of trust. I spent quite some time with Maria and her family before I asked her anything about the massacre, and I spent time in the community just being there as well. Once I thought that I had built up her trust, I asked her and she accepted. Because she had not spoken about it for so long, I though I would have to ask her a few gentle questions before really getting started. But it took only one question and she started. It became like a confessional; sometimes as a filmmaker you feel like a priest in a confessional.

Spectre: Her anguish shows in her hands; she is constantly moving them.

NH: She is an amazing beautiful woman. The good thing about her is that she has had two children since then, and she is an optimistic woman in a way. It was dreadful what occurred, but life does go on.

Spectre: That comes across in the film’s women; there are almost no tears during the burial scene, only one woman is crying. It shows the sense of strength, of moving on as you say. Maybe it’s due to a fatalistic world view, but it is very moving when you see this. It does make you feel useless. NH: I don’t know if it is fatalistic but I actually think there is something unique about the Acteal massacre. There have been other massacres in Latin American as well – in El Salvador, in Nicaragua – but this community has taken ownership of the massacre and turned it around into something that strengthens them. They are now called the Martyrs of the Sacred Land of Acteal. They have a curious mix of Catholicism and Mayan beliefs. The dead haven’t really died in our sense. There are animistic beliefs and it is believed that the souls of the dead continue in the wildlife so for them there is always this possibility that the dead are with them. We don’t really share that view and we are the ones that are more fatalistic. For them, this is just part of the great cycle that continues on and it strengthens them. People generally come away from Acteal feeling hopeful.

NH: I don’t know if it is fatalistic but I actually think there is something unique about the Acteal massacre. There have been other massacres in Latin American as well – in El Salvador, in Nicaragua – but this community has taken ownership of the massacre and turned it around into something that strengthens them. They are now called the Martyrs of the Sacred Land of Acteal. They have a curious mix of Catholicism and Mayan beliefs. The dead haven’t really died in our sense. There are animistic beliefs and it is believed that the souls of the dead continue in the wildlife so for them there is always this possibility that the dead are with them. We don’t really share that view and we are the ones that are more fatalistic. For them, this is just part of the great cycle that continues on and it strengthens them. People generally come away from Acteal feeling hopeful.

Spectre: This comes across in the film very will.

NH: We tried very hard to communicate that and to position the massacre in the way that they do themselves.

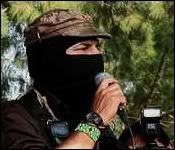

Spectre: In the documentary you say that Mexico wanted this land for development. What type of development? Sub-commander Marcos [spokesperson of the Zapatista Movement] talks about the right of indigenous peoples to make their own decisions, that they decide who they want to use their land. What does the Mexican Government want to do with Chiapas? Do they want to build it up for tourists because it is so beautiful?

NH: There is the tourist element but there are a lot of resources in Chiapas such as uranium and oil. Tabasco, an oil rich state, is just above Chiapas. And in the north there are supposedly uranium deposits and potentially natural gas deposits as well. The state oil company [Pemex] comes in and basically wants to set up test sites and start drilling, and they want the mineral rights to the land. Then there is the plan to turn the whole of Mexico and Central America into one free trading zone. This means creating roads and infrastructures that would allow more freight to cross which means that they cut though large parts of Indian land. The big problem with all of this development is that Indians are never asked and they don’t benefit, so they feel that everything is for the modernisation of Mexico, and they have no role.

Mexico’s grain comes from the United States and there are no more subsidies for agriculture – yes so they have been forced off their lands because they can’t get a price for their crops. They are not given any work in the development, so they have two choices. Go north and beg in the streets of Mexico City or further north and work on farms in California. Or they stay and fight. And that is how the Zapatistas have gained so much support. Because people are desperate, not because they are naturally rebellious. So their acts were acts of desperation initially.

Spectre: Chiapas is now occupied by the military. I think that there are anywhere from between 30 000 to70 000 Mexican troops there today.

NH: There is an enormous number of troops there. With the Fox government, there was some movement as to where they were positioned. It is not quite as intimidating as it used to be but there are enormous amounts of troops and it is a form of occupation. The Zapatistas have their autonomous zones which they continue to govern and run using their own form of government, but these are still effectively zones of occupation.

Spectre: How do you see the future for groups who want indigenous rule, such as the Zapatistas and the Abejas? Are they losing or gaining ground? NH: The Zapatistas are very good at stepping outside the region and reminding people of the issues. The part about Marcos you see in the film is continuing. I think the fact that the latest election was so tarnished with fraud that the Mexican people now feel dejected. Everyone was so extremely optimistic that the left-wing candidate would win and open a door and so they felt robbed in the end. There was a large left-wing constituency who went for the legal electoral routes, which didn’t work, and they feel extremely frustrated. Now the Zapatistas are offering this alternative form of democracy, and I think they’ll receive more support now because people feel that they have tried the official routes. The other routes are not about violence, they are still talking about civil society. A lot people are keen to try this autonomous self-governing possibility because the official route hasn’t worked. So I think that in large-scale political terms and in democratic terms within Mexico the Zapatistas are still offering this viable option which more people want to explore.

NH: The Zapatistas are very good at stepping outside the region and reminding people of the issues. The part about Marcos you see in the film is continuing. I think the fact that the latest election was so tarnished with fraud that the Mexican people now feel dejected. Everyone was so extremely optimistic that the left-wing candidate would win and open a door and so they felt robbed in the end. There was a large left-wing constituency who went for the legal electoral routes, which didn’t work, and they feel extremely frustrated. Now the Zapatistas are offering this alternative form of democracy, and I think they’ll receive more support now because people feel that they have tried the official routes. The other routes are not about violence, they are still talking about civil society. A lot people are keen to try this autonomous self-governing possibility because the official route hasn’t worked. So I think that in large-scale political terms and in democratic terms within Mexico the Zapatistas are still offering this viable option which more people want to explore.

In local terms, I think the self-government experiment is doing very very well in Chiapas. There are more and more of the communities created by 5 or 6 zones of self-government. Initially it didn’t work very well because they changed governors every couple of weeks as part of the experiment with citizens. But over the years, it has started to work and even the groups which were initially opposed, even party supporters [the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI)] have now come to work with the Zapatistas because they can’t be bribed. If they make a ruling they stick by it whereas the official system can be corrupted. So it’s very interesting. It is a classic misconception that from the outside it always looks lost, but from the inside there are always things going on that are quite optimistic. The locals themselves always say that as long as they’re fighting and experimenting they are winning. And Chiapas is an example of how you have to settle for smaller victories. It used to be that the traditional left wanted big victories where the proletariat would always win. But the Zapatistas are not your classical Marxists leftists and they basically say: “Look, let’s be happy with smaller victories and let’s keep on building coalitions.”

So there a lot a reason for optimism, but you have to be cautions because the right wing did win …

Spectre: Barely …

NH: Barely … but none the less they won. There is a strong element in Mexican society which has to do with drugs and corruption. There is a lack of rule of law and a lack of transparency in the political system and that is always dangerous. People are more and more frustrated with it.

The Chiapas movement keeps saying “We want to run things ourselves; if you want to give us funds fine, but let us organise it”. The government still uses whatever development projects they have as a form of control and clientism. We give you this if you give us your support and vote. Aid is never free in Mexico and a lot of it, along with development, has been politicised.

Spectre: Is there still a lot of discrimination against Indians? NH: Yes, as it sort of shows in the film Mexico is still a hugely racist country. People don’t realise it because it is brown and brown so it’s not as visible, but the indigenous are still very discriminated against. And many in the film you saw speak 6 or 7 indigenous languages. Some of the men can’t read or write, but they are far from being ignorant people. So in some ways the Zapatista rebellion is a form of cultural revolution that it is changing the way that the indigenous are perceived. Of course it is radical because if you truly accept the indigenous on their own terms, then you have to question what is accepted as development. They don’t want to join the official model of the government. Not because they are backward, but because they don’t see that as a progressive model for them.

NH: Yes, as it sort of shows in the film Mexico is still a hugely racist country. People don’t realise it because it is brown and brown so it’s not as visible, but the indigenous are still very discriminated against. And many in the film you saw speak 6 or 7 indigenous languages. Some of the men can’t read or write, but they are far from being ignorant people. So in some ways the Zapatista rebellion is a form of cultural revolution that it is changing the way that the indigenous are perceived. Of course it is radical because if you truly accept the indigenous on their own terms, then you have to question what is accepted as development. They don’t want to join the official model of the government. Not because they are backward, but because they don’t see that as a progressive model for them.

We have just launched our website:

Spectre: Do you know the French historian Mark Ferro? In writing on history and film, he points out that film is one way of giving alternative versions to official versions of history, and of giving a voice to marginalised peoples.

NH: Those were absolutely my motivations.

The Edinburgh International Film Festival, Août 2007.

Butterfly Woo Dip pour Les Films du Spectre (Strasbourg).

Autorisation pour toute reproduction de cette interview (dans son intégralité ou pour une partie de cette dernière) à obtenir de consuelo.holtzer@gmail.com Traduction en cours...

Traduction en cours...

Entretien avec Nick Higgins

Inscription à :

Publier les commentaires (Atom)

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire